We often train our physiological systems for racing, but what about training for mental toughness? Can that be trained?

If you’ve competed for any amount of time, you know in almost every race something unexpected happens.

- In a road race, someone attempts a break at an unexpected time and must be chased down.

- In a triathlon, you have a mechanical failure or an unforeseen crosswind.

- In an ultra-distance, you hit the wall and need to push through.

The ability to mentally cope with the unknown and unexpected is vital to race success.

A Deeper Look at Mental Toughness in Cycling

Gucciardi, Hanton, Gordon, Mallett, and Temby (2015) state mental toughness is “a personal capacity to achieve consistently high levels of subjective (e.g., personal goals or strivings) or objective (e.g., sales, race time, GPA) performance despite everyday challenges and stressors as well as significant adversities.”

Gucciardi, Peeling, Ducker, and Dawson, (2016) suggested that researchers (e.g., Hardy, Bell, & Beattie, 2014) have recently focused attention on the observable behaviors or actions that are typically demonstrated in challenging or demanding situations. For example, mental toughness might be associated with perseverance, effort, and persistence in the face of adversity.

Gucciardi (2009)Gucciardi (2009) suggests that rather than treating mental toughness as an objective personality construct or a post hoc explanation of a given behavior, researchers should consider mental toughness as a process that involves person-situation interactions. (source)

If mental toughness is a process that relies on person-situation interactions, then it can be trained.

Jones, Hanton, and Connaughton (2002) have a strong paper looking at Olympic athletes and mental toughness. Their definition that emerged from the procedure described previously was as follows:

Mental toughness is having the natural or developed psychological edge that enables you to:

- Generally, cope better than your opponents with the many demands (competition, training, lifestyle) that sport places on a performer.

- Specifically, be more consistent and better than your opponents in remaining determined, focused, confident, and in control under pressure. (source)

Flow-State and Mental Toughness

Sports psychologists mention that, in the best performances, athletes talk about being in the flow – a state of near auto-pilot. Flow is a state of mind in which one acts with minimal conscious intention or awareness and where we aren’t having to overthink the execution of the race plan or technique.

The unknown and unexpected interrupts this flow. When unexpected or unknown scenarios occur in a race, we often get out of the flow and start thinking about specifics as the mind has a tendency to panic. We begin to question ourselves as anxiety rises. The best racers know how to quickly return to Flow-State.

To maintain or regain the flow, the racer needs:

1. The ability to quickly reframe a response to the unexpected.

Peyton Manning was famous for coming to the line of scrimmage and audibling the play call, depending on what the defense showed. The same is true in endurance sports, except the defense is other riders, your equipment, the course, and conditions.

I had a mechanical in a 12-hour ultra, which costs me twelve minutes. What do I do now? Should I attempt to make up lost time over the duration of the rest of the race? Do I go harder for the first 30 minutes or disperse it over the remaining time?

We were all expecting the break attempt at the bottom of the third climb, but a strong rider went early, and now what should I do? Can I sustain a chase? (Riders did not do this decisively in the famed 2006 Tour de France: Stage 17, when Floyd Landis went way earlier than the peloton expected. Caveat: Yes, Landis was doped and so were all the other leaders. I’m not excusing that.)

2. To confidently continue into the unknown.

Confidence comes from predictability. Predictability comes from successfully navigating previous responses to adapting and overcoming the unknown.

Have I overcome surprises relatively well before?

What happens to my mental state when things do not go according to plan? Do I freak out?

These two elements working in tandem are often referred to as resilience, grit, or mental toughness.

What is One Way to Mentally Train for the Unknown?

Obviously, sabotaging someone’s bike to break mid-training session isn’t prudent. And as a coach or athlete, you’ll never be able to replicate every unknown or unexpected race scenario that might emerge. That’s why race experience is so valuable.

BUT we can approximate training for the unexpected and unknown to a degree. We know this works because the military branches, particularly the Navy Seals use this method. They cannot place a candidate in a real battle. However, they place them in unfamiliar and unknown circumstances. These approximate similar mental strains they will face in battle. An example is the famed hold-the-log-as-a-unit-until-we-say-put-it-down drill.

It is doubtful, a group of Navy Seals will need to hold a log over their head for 3 hours in battle. That’s not the point of the exercise. It’s to develop the mental toughness to persevere when your body is screaming LET’S QUIT!

We’ve developed a method we’ve deem PUC Intervals (short for Polarized Unknown Chaos) to help mental preparation, toughness, and resilience along with practicing remaining in Flow-State even when facing the unknown.

Using Polarized Unknown Chaos Intervals (PUC) Intervals.

PUC Interval sessions are simply this:

The athlete completes a session “blind,” not knowing where they are in the current interval and what intervals lie ahead. They have no workout roadmap or session schedule. They must mentally press through the unknown session. The next interval may be 1 minute at 120% of VO2max or 5 minutes at 95% of VO2max. The recovery between a given interval may be 4 minutes or 30 seconds.

PUC sessions work best with a smart trainer in ERG mode to control the resistance and wattage output. The cyclist needs only to spin at a given cadence regardless of what is thrown his or her way during the session.

The intervals are highly randomized to a point where the athlete cannot figure out any pattern.

We typically construct these using a polarized model (easy <65% of Vo2max or hard >85% of VO2max).

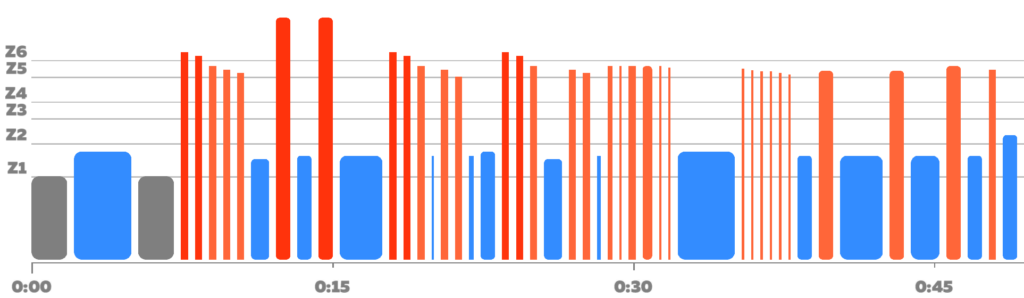

Here is the layout of a hypothetical PUC session:

You can see how the session is exceedingly random in its structure. It’s definitely not a 1-minute-on, 1-minute-off session.

Since the athlete is riding the entire session blind, he or she will have no measure of how long the current interval will last, how long the recovery interval will be, or what will follow. They must simply maintain cadence throughout the entire session, trusting their coach—or the workout designer—has designed a workout they can complete physiologically.

The only limiter in a PUC session is their mental toughness in dealing with the unknown. Knowing this in advance makes the athlete prepared for a mental battle.

How do these translate to IRL racing?

In real life competitions, when facing the unknown, the tendency is to think, “Oh no, I don’t know how this will affect me, maybe I should back off and keep something in reserve?”

When we are fatigued, we quit making good GRIT decisions. Our brain says, “Stop or slow down.”

In a PUC Interval session, the athlete cannot back off or keep something in reserve since they are on an ERG at a given cadence. They can and must endure the session while mentally pressing through any unknowns.

This trains mental toughness. It builds grit. And as a side benefit, they are solid VO2max sessions.

Grab These Free Sample PUC .ZWO Workouts

Feel free to download these sample Zwift workouts (they also work on TrainerRoad, etc.). Remember to not open them and look at them yourself, since that will tip you off to what is coming. Have a friend, coach, or loved one upload these to Zwift, set your FTP if needed, and start the session for you. You should not be to see the Zwift (or other platform screens) in any way.

Download the PUC Intervals .ZWO files from the Google Drive Folder Here

A decently trained rider should be able to complete these since your coach or workout-opener-person will adjust to your FTP.

For instructions on how to install these workout in Zwift, check out: https://support.zwift.com/en_us/workout-mode-S1WDxDuNB

To launch and/or change FTP for the workout we’ve made a video for a non-Zwifting spouse or friend since you shouldn’t see the workout profile.

These sessions should be very tough but completable. If you find them too easy around 30 minute in, have your launching person slide up the FTP slider or have them session up to 10% on the Companion App.

What We’ve Learned by Doing PUC Sessions

These session have definitely benefited the riders who have completed them. Things we’ve learned include:

- Most of our “quit” is mental. When our mind is “done,” we almost always have much more in the physiological tank.

- You can train mental toughness by placing yourself in challenging mental situations. It’s a learned behavior, not just an innate ability.

- We’ve been able to apply the learned grit to gain confidence when the unknown or unpredictable occurs in a race. We think, “I’ve mentally handled this type of challenge before. I can do it again!”

As a related note, a pro-team actually went through Navy Seal training for mental toughness. Read their experience here.

Let us know what you learn from your PUC interval sessions in a comment below. What other tips do you to develop mental toughness?

Jordan Fowler has experience as a head swimming coach of the Frisco Swim Team, a TAAF-awarded coach, a track and field distance running consultant for select Texas High School runners, and has competed as a triathlete, road runner, and cyclist. Though he is remarkably slower than he was in his 20s and 30s, he still enjoys endurance sports and sports science studies.